Articles

This opinion considers whether, under section 51 of the Basic Education Laws Amendment Act (“the BELA Act”), parents who provide home education may freely choose an educational curriculum.

It examines the interaction between sections 51(2)(b)(i) and 51(2)(a)(iii), the scope of administrative discretion conferred on provincial authorities, and the implications of vagueness for both administrative approval and criminal enforcement.

Statutory framework

Section 51(2)(b)(i) of the BELA Act requires parents to undertake to: “make suitable educational resources available to support the learner’s learning.”

Section 51(2)(a)(iii) requires that the Head of Department (“HOD”) be satisfied that: “the proposed home education programme is suitable for the learner’s age, grade level and ability and predominantly covers the acquisition of content and skills at least comparable to the relevant national curriculum determined by the Minister.”

Parental choice of curriculum is therefore subject to approval based on both learner suitability and national curriculum comparability.

Constitutional principles engaged

The provisions under consideration engage several foundational constitutional principles, including:

- The principle of legality and the rule of law (section 1(c));

- The right to lawful, reasonable, and procedurally fair administrative action (section 33);

- The best interests of the child (section 28(2));

- Freedom of conscience, belief, and opinion (section 15), insofar as curriculum choice reflects philosophical or pedagogical convictions;

- Parental responsibility and care, as recognised in constitutional jurisprudence relating to family autonomy.

Any statutory scheme that limits parental decision-making in education must therefore be sufficiently clear, rational, and proportionate to withstand constitutional scrutiny.

Vagueness and the principle of legality

The requirement that a home education programme must “predominantly” cover content and skills “at least comparable” to the national curriculum is undefined and indeterminate.

The Act does not specify:

- What degree of alignment constitutes “predominant” coverage;

- How “comparability” is to be measured;

- Which elements of the national curriculum are essential or non-essential;

- How alternative pedagogical approaches are to be assessed.

The Constitutional Court has consistently held that laws imposing obligations on citizens must be stated with sufficient clarity to enable compliance. Vague laws undermine the principle of legality, a core component of the rule of law.

Where compliance depends on the subjective satisfaction of an official without objective criteria, affected persons cannot reasonably predict the legal consequences of their actions. In this context, parents cannot determine in advance whether their chosen curriculum will be approved, despite acting in good faith.

Subordination of parental judgment and the best interests of the child

Section 51(2)(b)(i) recognises parental responsibility to select resources suitable for the learner. However, section 51(2)(a)(iii) effectively redefines suitability through alignment with the national curriculum.

This creates a structural tension:

- Individual learner needs, abilities, and educational contexts may justify a curriculum that diverges from the national model;

- Yet approval hinges on national curriculum comparability, irrespective of demonstrated educational benefit to the learner.

Section 28(2) of the Constitution provides that the best interests of the child are of paramount importance in every matter concerning the child. Home education is inherently individualized, and parental decisions regarding curriculum are often motivated by the specific educational needs of a child.

A statutory framework that prioritises systemic curricular conformity over individualized educational suitability risks elevating administrative convenience above the best interests of the learner. At minimum, the Act provides no guidance on how these interests are to be balanced.

Administrative discretion and constitutional administrative justice

The broad discretion afforded to HODs by section 51(2)(a)(iii), in the absence of objective standards, raises concerns under section 33 of the Constitution.

- Unstructured discretion creates a material risk of:

- Inconsistent decision-making across provinces;

- Arbitrary or subjective refusals;

- Unequal treatment of similarly situated parents.

Administrative justice requires that decisions be capable of rational justification and meaningful review. Where the statutory test itself is undefined, both decision-makers and reviewing courts lack a principled basis on which to assess compliance.

This undermines transparency, accountability, and fairness in the registration process.

Criminal enforcement, fault, and “just cause”

Failure to register a home learner constitutes a criminal offence, subject to a defence where parents have a “just cause” for non-registration.

Criminal liability requires that obligations be clear and ascertainable. Where registration depends on uncertain approval criteria and unpredictable administrative discretion, parents may reasonably be deterred from applying, particularly where rejection could expose them to further regulatory consequences.

In any prosecution, the state must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the accused lacked just cause. Given the vagueness of the curriculum approval requirement, and the absence of objective compliance standards, establishing the absence of just cause would be evidentially challenging, especially where parents acted bona fide in the educational interests of their children.

Conclusion

It is the considered opinion that section 51 of the BELA Act materially restricts curriculum choice for home educators through vague and undefined approval requirements tied to the national curriculum.

These provisions engage and potentially undermine constitutional principles of legality, legal certainty, administrative justice, and the best interests of the child. The absence of objective standards creates scope for arbitrary administrative action and weakens the enforceability of criminal sanctions for non-registration.

Unless clarified through precise regulations or authoritative guidance, section 51 is likely to generate legal uncertainty, deter lawful compliance, and invite constitutional challenge.

Legal & Research

Homeschooling and the law

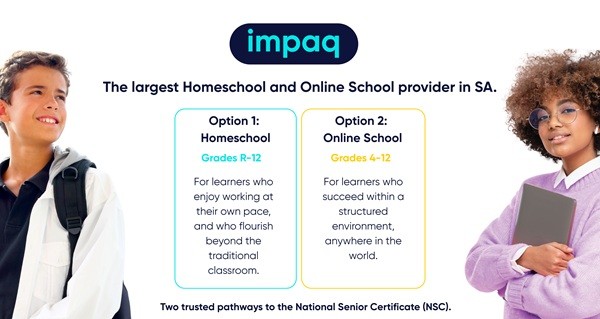

Home schooling was recognized in 1996 in Section 51 of the SA Schools

+ ViewCentres

Support

Curriculums

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Do homeschoolers take holidays?

Yes, they take breaks. Some homeschool families follow the public school year calendar especially if they are involved in sport and music...

-

How does homeschooling work?

Homeschooling is different for every family as it depend on the parents educational goals for their children Education is the development of the...

-

Can I be a working mom and homeschool?

Single parents who are committed to homeschool organize a schedule around their work commitments and sometimes involve family or tutors to assist...

-

Is home education often used as a smoke screen to hide child neglect?

State interference in home education is often justified as something that can identify situations where home education is used as a smoke screen to...